The NEUtrino invention

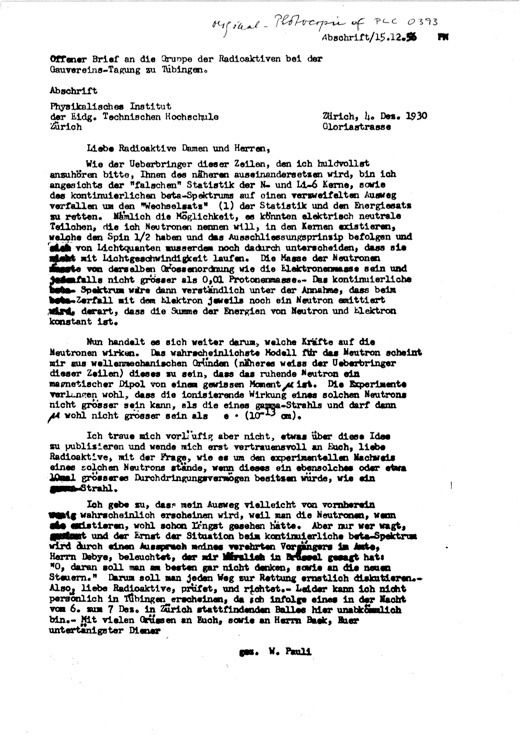

A machine-typed copy of Pauli’s famous letter sent to the scientists attending the Tübingen meeting in 1930.

a bold idea to save energy conservation in beta decays:

Wolfgang Pauli, at age 30, had a bold idea on how to solve a perplexing problem in nuclear physics. To explain the apparent disappearance of energy in the decay of certain atomic nuclei, he postulated the existence of a neutral, light-weight particle, saving the fundamental law of the conservation of energy. Pauli proposed that “neutrons” could emerge from decay processes, carrying away energy while escaping direct experimental detection.

Worried that nobody would ever be able to observe this particle, Pauli did not dare to publish his invention without consulting some experimental physicists. On December 4, 1930, Pauli wrote an open letter to a group of nuclear physicists, the “dear radioactive ladies and gentlemen,” who were going to meet a few days later in Tübingen, Germany. The document (see below) is a machine-typed copy that Pauli obtained in 1956 from Lise Meitner, a well-regarded scientist who had attended the Tübingen meeting.

In the early 1930s, scientists elaborated on Pauli’s idea and concluded that the new particle must be extremely light and very weakly interacting. When James Chadwick discovered a neutral particle in 1932, it received the name neutron. But the particle turned out to be too heavy to fit Pauli’s prediction. Enrico Fermi, developing a theory of weakly interacting particles, introduced a new name for Pauli’s particle: neutrino, which means “little neutral one.” A quarter-century later, scientists observed for the first time collisions of neutrinos with matter, the long-sought-after evidence for Pauli’s ghost-like invention.